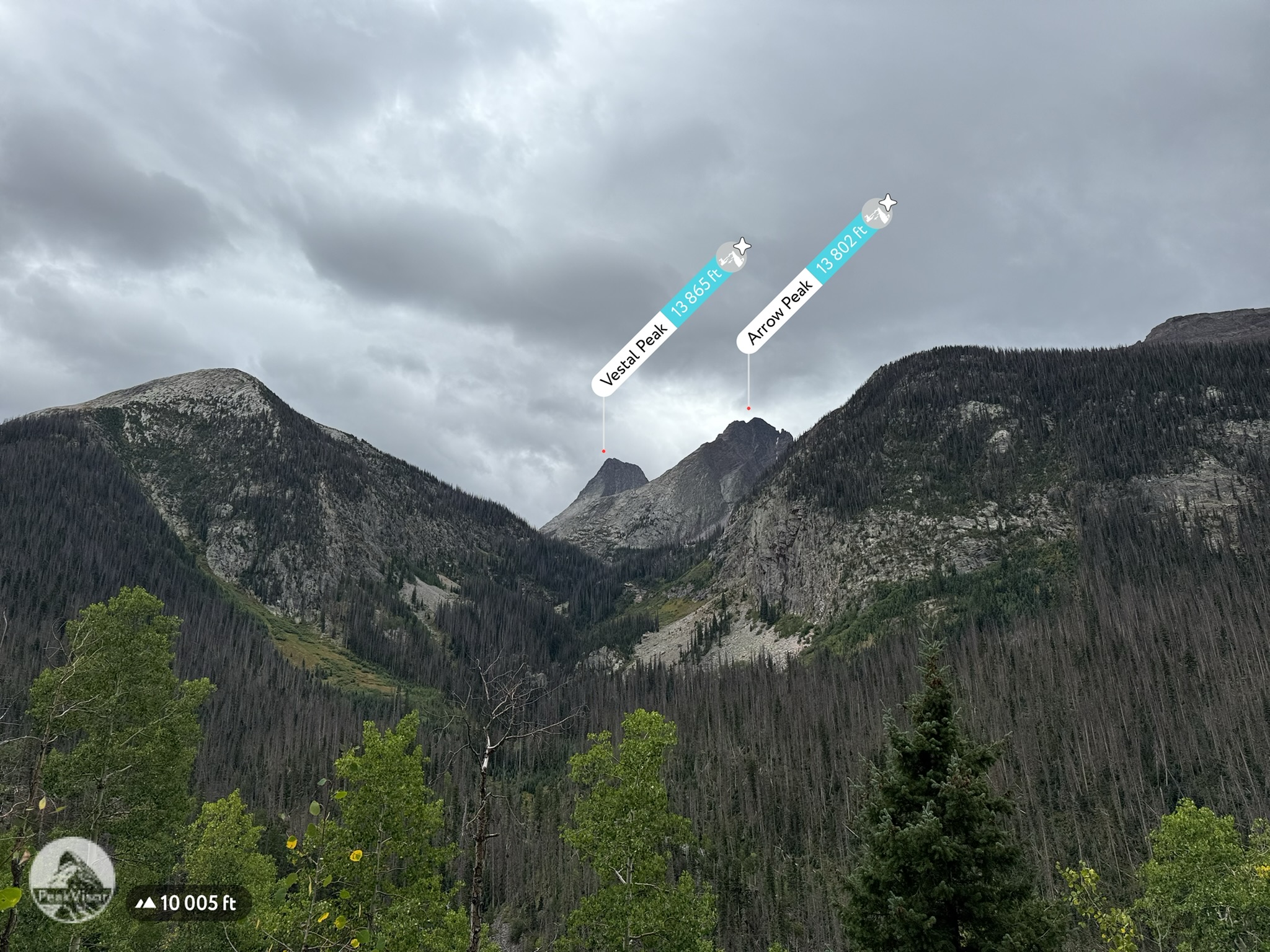

Over the Labor Day weekend, we headed down to the Vestal Basin in the Grenadier Range. On the 10 mile approach from Molas pass along the Colorado Trail, on Friday, we started to get glimpses of the mountains we planned to climb as we hiked through light rain. Ripe raspberries were scattered in patches along the trail, making for a great trail snacks. Almost as soon as we made it to the meadow at 11500' and set up our tent, the rain began in earnest: the perfect soundtrack for an afternoon nap.

Saturday had the driest forecast of the weekend so we woke up at 4:30 AM to begin the approach to the Trinity Traverse, a stunning class 4 ridge that crosses the emonymous Trinities: West Trinity (13765'), Trinity (13805', the 100th highest peak in Colorado according to Lidar), and East Trinity (13752). Creativity: not the strong suit of peak names.

Once in the upper basin, there are no established trails as humans make little impression on talus fields. We made our way up past Vestal Lake, and could just glimpse the summits of the 3 Trinity peaks to our east catching the morning light. We picked what we hoped was the least-terrible gulley to ascend to the ridge. We skittered our way up the icy talus and scree, hoping that traction would improve once the sun cleared the Trinity peaks.

As we gained the ridge just after 8 AM, we were rewarded with expansive views of the Needle Mountains to our south, including the four Chicago Basin Fourteeners. Down into the basin to our southeast, Balsam lake’s surface was deep blue. The glaciers are long gone, but the glacial flour still in suspension in the lake gives it a turquoise hue. We stopped at the saddle to have a quick breakfast and wait for the sun to melt off the ice from the previous day’s rain. Finally, we were ready to begin the traverse.

Finally: scrambling. We stayed on the ridge proper as we ascended to West Trinity. The rock was surprisingly solid and the difficulty never exceeded class 3, with mostly class 2. The summit provided excellent views of Arrow and Vestal to the west. A summit register in a plastic jar showed the most recent ascent was on 8/24, the weekend before.

The scrambling increased in difficulty as we traversed to Trinity Peak, the shortest Colorado Centennial but the high point of the traverse at 13,816 feet. We worked our way along grassy ledges south of the ridge. On one of these grassy slopes, nestled among boulders, we came upon an Engelmann Spruce at 13,420 feet, one of the highest trees we’ve seen in Colorado. Tree line in the Colorado Rockies varies by aspect, climate, and other factors but is typically above 11k but below 12k feet. Perhaps the presence of this hardy little guy is a vanguard of climate change.

We continued along a sparsely-cairned route until we reached the first crux of the day, a 40-foot near-vertical class 4 chimney. It’s remarkably difficult to capture the steepness of scrambling routes in 2d pictures but a fall here would be a bad day.

Still, climbing a chimney narrow enough to stem up always feels remarkably secure. (Stemming is a climbing technique that involves using the body to push against opposing surfaces.) Once on top of this section, the scrambling to the summit was straightforward and we soon found ourselves on the high point of the traverse: Trinity Peak (13816) at 12:20 PM.

We paused for something between a snack and lunch while taking our first good look at East Trinity. From our vantage point on the summit, it presented a daunting face that appeared to be nearly vertical. This is largely a problem of perception, as both the foreshortening effect and viewing angle causes the mind to overestimate slope angle. Clinging to our knowledge that the route doesn’t exceed class 4, we started down the steep gully to the saddle between Trinity and East Trinity.

From the base of the wall, it suddenly looked far less daunting (although this is also an illusion and the truth lies somewhere between the two extremes of perception.) The climbing was sustained and focusing, so we didn’t stop for pictures until the summit. The top of the gully we ascended topped out with some airy class 4 moves.

As we neared the top of the gully ascent of East Trinity, we heard rock fall from the gully we had just descended off of Trinity and traced the source to the only other climber we saw on the traverse. A woman was running down the class 3 gully, scattering loose rocks as she descended. When she caught up to us on the final descent of East Trinity, we found out she was running all 5 peaks in Vestal Basin, starting at the trailhead that morning, for a total of 30+ miles and 12k feet of elevation. In Colorado, there’s always someone going bigger than you are.

We stopped briefly at the summit of East Trinity, then started the long descent back down into Vestal Basin. Looking back at Trinity Peak from East Trinity, it presented a similarly-vertical face.

The climbing was over, but the technical terrain was not. There was still plenty of scrambling requiring our full attention before we made it back down to the comparative flat of Vestal Basin.

Once down, we stopped at Unnamed Lake 12396 in the upper basin to filter water and consider our options. 3 PM, still 5 hours of daylight left. We had originally planned to climb the remaining two peaks in the basin, Vestal and Arrow, on Sunday but knew that would be a big day even if the weather held, and that is never certain in the Needle Mountains in August. As there appeared to be no thunderstorm development, we decided to attempt to climb Arrow Peak at the opposite end of the basin. We traversed across the basin for 2 miles, picking our way through a mix of talus and glacier-scraped rock. The bedrock still showed the direction of glacial movement in the deep grooves cut by rocks embedded in the base of the glacier.

About half way through the basin, we encountered a Ptarmigan, camouflaged to invisibility in its brown summer plumage. Reluctant flyers, this one simply ran away from us. Not wanting to disturb it, we decided to give it a wide berth and detoured to our left away from the bird. Unfortunately this was the exact wrong direction. It had been leading us away from its nest, and our detour took us right to the nest under a boulder, so well-hidden we would have missed it if two nearly-grown chicks had not emerged just as we walked by it. The other parent apparated from the tundra as we made a swift exit.

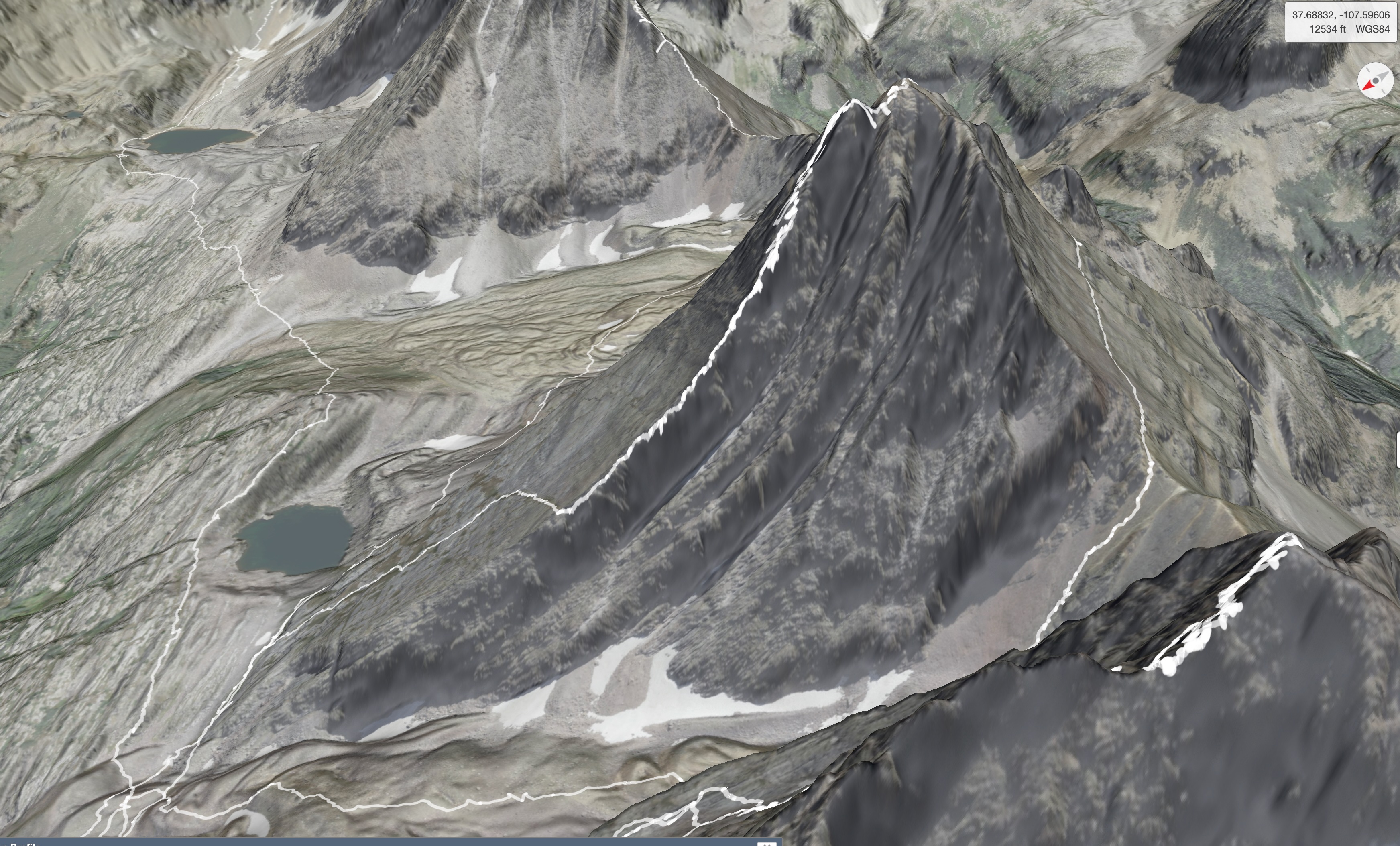

Arrow Peak via the Northeast Face is one of the singular climbs of any Colorado Centennial. At 13817 feet, it is just one foot higher than Trinity Peak, making it the 99th highest peak in Colorado. Like Vestal Peak, it is composed of uplifted Precambrian quartzite of the Uncompaghre Formation dated to 1.8 billion years old, that steepens with elevation. The route follows a rib of rock that forms a nearly-smooth ramp curving relentlessly toward the summit over a distance of 1.2 miles and 1700 feet. This ramp can also serve as a bowling alley for rocks dislodged from above so we were glad that we were the only party on the mountain as we started the ascent. Glad for the sticky Vibram soles of our La Sportive TX4 approach shoes, we started up the incline, calves burning. The 3D map shows our GPS track to the summit.

From the ramp on Arrow we had spectacular views of Vestal, our objective for the next morning, with the Trinities behind. As it loomed over our route, the thought of ascending the North Face of Vestal was intimidating. Racing the waning light, we took few photos on the ascent. Near the top the ramp gives way to a well-cairned route that steepens to class 3 and then class 4. After I made a couple of false detours that verged into 5th class terrain, we made it to the summit at 6:10 PM and took a hasty summit photo, squinting into the evening sun for the Vestal backdrop.

After 5 minutes at the summit we started our descent, watching the lowering Sun play over Vestal.

I was mesmerized by Vestal in the changing light, and took frankly-embarassing number of photos as we descended back into Vestal Basin. Beyond Vestal, the Trinity Peaks caught the last rays of Sun.

As we neared the bottom of Arrow's ramp, we noticed a family of mountain goats in the basin below, waggling their fat autumn butts as they ran away.

The sun set just as we exited the bottom of the ramp back into Vestal Basin at 7:40 PM. From there we could see the tents of other climbers in the basin below, not far from our campsite in the trees. Back at our tent by 8:15 PM we ate our dinners of Spicy Grilled Chicken Curry (Randall) and Forever Young Mac and Cheese (Maya) then crashed, hard.

Sunday: Wham Ridge

Sunday morning broke cold and clear, with the undercurrent of anxiety that precedes a dangerous climb. The overnight low in our tent was 34F, and we were glad to sleep in until sunrise at 6:40 AM. Following our morning ablutions and a hasty breakfast of leftover chocolate mudpie and Cheez-its (the breakfast of champions) we emerged to from our goose-down cocoons to see other bleary-eyed campers starting their days. I stopped by the tent of a pair of guys who had climbed Vestal the previous day to glean what beta I could—they were headed out of the wilderness to the nearby hot springs, which sounded more enticing than our plans—then back to our campsite to pack up the climbing gear.

In addition to our backpacking gear, we hauled 18 pounds of climbing gear in for the ascent of Vestal’s Wham ridge, a classic 5.4 line up the north face (see the Yosemite Decimal System for a detailed description of climbing grades). 5.4 is not particularly difficult climbing, and we had soloed (climbed without a rope) low 5th class terrain on previous alpine climbs, but the sustained nature of this route and the fatal consequences of a misstep convinced us to haul this extra gear, increasing our margin of safety.

Harness, Randall: 14 oz Harness, Maya: 15 oz 60 m Mammut Crag Dry rope: 8 lb 6 oz Minimal alpine trad rack: 7 lb 2 oz Black Diamond Helmets (each): 8.5 oz Alpine Trad rack: Alpine slings (8) Alpine double slings (4) Wildcountry friends Cams: 0.3–3 (doubles of 0.75–2) Tricams: set of 3 Nuts: full set Personal Anchor System (2) GriGri belay device ATC belay device Camp Piu belay device Hollow Block Prussik loop (2) 180 cm slings for anchor building (2)

I was glad for our ultralight equipment and my carefully-optimized backpacking base weight of 10 pounds (this means my pack weights 11 pounds before food, water, and of course climbing gear).

Another reason to carry the gear was to be able to rappel off of the route in case of bad weather. More than one climber has died on this route when a thunderstorm blew in, turning the quartzite into a treacherous slide, slippery as glass. Having the gear meant that we could always place anchors and rappel back to the base.

Maya carried the 60 meter rope, I carried the trad gear, and we made our way back up the headwall to the base of Wham Ridge by 8:45 AM, a vantage point no less intimidating than our views from Arrow the previous evening. Suddenly, I had to poop.

That done, we took a photo for forensic evidence and started up the relatively gentle lower slopes, following a grassy crack that angles up and to the right along the ridge. Near the top of this feature, we stopped to rack up, putting on our harnesses and clipping the equipment to them so that we’d be ready to rope up when necessary.

We continued up, following the arete that forms the western edge of the north face as it steepened, following the crack systems that provided the easiest climbing.

The angle gradually increased to just a few degrees off-vertical but the vertical cracks continued to provide good holds.

As the cracks narrowed and the holds thinned, we decided to rope up for the steepest pitches of climbing. Maya stood on a wide ledge that made for a good belay stance with the rope through her GriGri belay device, and I started up the wall with the rope attached to my harness, placing gear (primarily cams) in cracks to arrest a potential fall. (Picture of cam included to demonstrate how they hold in the rock.)

I ran the first pitch out most of the 60m length of rope until I came to another ledge large enough for two people, where I built an anchor by slinging two boulders, and belayed Maya up on top rope until she reached the anchor. We repeated this for 3 pitches until the angle relented slightly and we unroped for the summit pitches.

The summit pitches, though not as exposed as the ridge, were no less fear-inducing and consequential, as evidenced by the lack of photos of that section. We were too gripped to document it.

The top out at 1:45 PM was cathartic.

We found the summit register, last signed by a couple from Utah who we had met at the base and had climbed up ahead of us. They wrote 'Free Palestine. Fuck ICE.'.

We took a few summit photos, gathered ourselves, packed away our gear, and started the chossy class 3 descent off of the south side of Vestal.

Near the summit, we saw a pika licking urine off a rock (good source of salt).

The descent, while not as focusing as the ascent, is long, loose, and chossy. At one point we “scree-skied” down a slope that was too loose to stand on, releasing a cascade of rocks.

Back to the meadow campsite by 4 PM. We packed up camp and started the hike out at 4:50 PM.

The hike out provided new angles on the mountains we had climbed. Even the Moon was checking out Wham Ridge.

We passed some massive avalanche debris on our way out, made it to the Animas River just as dark was falling, and set up camp for the night.

The next morning we made the 1700-foot 37-switchback ascent from the Animas River back up to Molas Pass and the trailhead. From there, we drove into Silverton for a breakfast of french toast, eggs, bacon, and buttermilk pancakes that I was too hungry to document.

Total mileage: 39 miles Total elevation: 13000 feet

Comments

Wow Rand! I loved reading your Vestal Basin trip report! Thank you for sharing. 💜